Imagine a time when you needed to know a martial art not just for sport, not to lose weight, but to survive in your daily life. Fight or die. This was the context of many people throughout our history, including the inhabitants of a small group of islands south of Japan. It was the independent kingdom of Ryukyu, the birthplace of Karate. Today, the Ryukyu Islands, annexed by Japan, correspond to the prefecture of Okinawa and have a very unique and rich history and culture.

Okinawa has a strategic position, as it is located in the middle of maritime trade routes for vessels coming from China, Japan and Korea, among other countries in East Asia and Southeast Asia. This provided a very strong cultural influence from these people in ancient times, both in their system of government, rituals, clothing and martial arts. As a result, techniques from ancient arts of the region, such as Tegumi (still practiced today), were mixed with methods imported from other countries to the Ryukyu Kingdom, forming a completely new art. The focus of this mixture was effectiveness, for the warrior to survive various approaches of aggression.

Yes, that’s right: Karate as we know it today developed from an amalgamation of several sources. And you thought mixed martial arts were something modern, didn’t you?

Chinese influence

It is impossible to trace the exact date of Karate’s origin. This is because it was not something that was born ready-made, but rather developed over the decades: each master brought his experiences and improvements that helped shape the main lines of the art. Furthermore, for many years, Karate was an art practiced in secret, behind closed doors. There were no dojos. For centuries, there were few written records about the art, until it began to be disseminated outside of Okinawa, at the end of the 19th century.

Going back in time to the Chinese roots of Karate, the techniques that came to form this martial art may have even more remote origins, around 1500 years old. This is if we consider the legend of the Zen monk Bodhidharma, who oral traditions say was responsible for introducing the Shaolin monks to the exercises that were the basis for Kung Fu and, consequently, Karate. However, this information is less factual. Documentation on martial arts in Ryukyu can in fact be found from the 17th century onwards, making Karate a centuries-old art, less than 500 years old.

The fact is that China had a very strong influence on Ryukyu, even more so than Japan. This is because for a long time there was a very close relationship of exchange between the two nations, with Chinese communities settling in Ryukyu and Ryukyu citizens traveling to China to study the arts and technologies. And this shaped the development of Karate, with Chinese masters teaching their techniques in Ryukyu and local practitioners seeking to deepen their knowledge in China.

An example of this tradition is the Sanchin kata, one of the oldest in Karate. Aiming to improve physical conditioning, breathing and concentration, the Shaolin monks of the Chinese province of Fujian developed the San Zhan (or San Chien) form, found to this day in Kung Fu styles such as White Crane. Karate masters (most notably Kanryo Higashionna) learned San Zhan and implemented it in Okinawa, giving their own interpretations to what came to be Sanchin, an important pillar for the line of Karate that emerged in the city of Naha, the capital of Okinawa.

The influence of Chinese arts was so significant for the origin of Karate that long before it had the name by which we know it, the art was known as Tode (or Toudi, in the Ryukyu dialect), which means “Chinese hand”. Another name by which the art was known was simply Te (hand), which sometimes served as a suffix for the different lines of Tode that were practiced. Thus, the Tode practiced in Naha could be called “Naha-Te”, while the school in the city of Shuri was “Shuri-Te” and in Tomari the school was “Tomari-Te”.

An evolving art

Tode did not remain confined to its Chinese roots. The Ryukyu/Okinawa resident masters were both warriors and researchers. Many of the more traditional kata drew from this multicultural source, but practitioners went further. They studied the techniques, the mechanics of the body, and adapted and interpreted everything with the aim, above all, of developing a direct and deadly art, an efficient self-defense.

An important factor in the consolidation of Tode and its sister art, Kobu-Do, was the need for self-defense among Okinawans without the use of swords and other traditional weapons. This is because the carrying of weapons was prohibited on the island on two occasions. The first was in 1507, by King Shō Shin, when all aji (feudal lords) had to hand over their weapons. The other was the total ban on weapons in 1609, during the Japanese domination of Ryukyu.

With these restrictions, the solution for self-defense, then, was to develop fights with empty hands or with unconventional instruments, such as oars and farming tools (Kobu-Do). Apparently, the person was unarmed, but their defensive potential was very great. Thus, the art developed in a veiled way, but became entangled in the culture of the region.

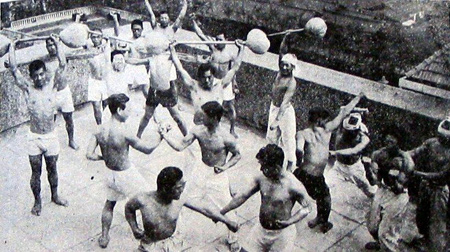

After the Meiji Restoration in Japan and the formal annexation of the Ryukyu Islands into the country in 1879, Tode began to be practiced more openly. Several masters contributed to the modernization and dissemination of the art, such as Kenwa Mabuni, Chōjun Miyagi, Motobu Chōki, Kanken Tōyama and Kanbun Uechi, among others.

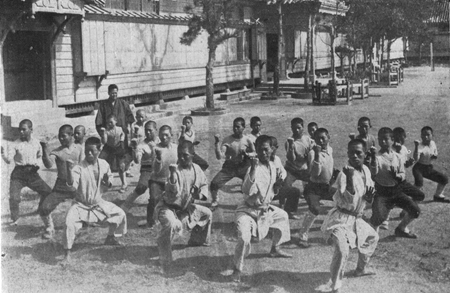

An important step was taken by master Itosu Ankō, who in 1902 worked to introduce Tode into the curriculum of the Okinawan educational system. He developed introductory kata that were easier for children to learn, and advocated the benefits of practicing Tode to Japanese authorities. But it was one of his disciples, Gichin Funakoshi, who succeeded in taking Tode outside his homeland, teaching the art in the Japanese capital, Tokyo.

Name change: Tode becomes Karate-Do

Funakoshi faced some challenges. An art called “Chinese hand”, full of techniques with names referring to Chinese culture, would not be very successful in Japan, which was a rival country of China. In addition, the teaching needed to be systematized so that it could be transmitted to large groups and schools, with a defined level of progression. So, nomenclatures were changed (such as the Pinan series of katas, which became known as Heian in Funakoshi’s school); the Judo belt system was adopted, with kyu and dan to determine the level of the practitioner; and the Judo training uniform, called dogi or keikogi (commonly known in Brazil as kimono) was adopted and adapted for Karate.

The solution to the problem of naming the art was an effective play on words. Several kanji, ideograms used in Chinese and Japanese writing, have more than one pronunciation for the signs. The characters that form the word “Tode” (唐手) can be read in an alternative way as “Karate”. It was from this pronunciation that the master used to modify the first kanji, “kara”, to another that had a different meaning, but the same sound. In its place was introduced the kanji that means “empty”. Thus, the new script for Karate (空手) came to mean “empty hand” instead of “Chinese hand”, highlighting the philosophical facet of the art. The change was quickly adopted by the Okinawan masters.

唐(chinese/China) 手(hand)

空 (empty) 手 (hand)

As an addendum to the introduction of Karate in Japan, it was necessary for it to be recognized as a “budo”, that is, a genuinely Japanese art. After the Japanese modernization that occurred as a result of the Meiji Restoration, traditional martial arts were given a makeover to survive in the new era: they stopped being just war arts and gained an appeal more focused on the personal development of practitioners. This led to the change of the word “jutsu” (technique) to “do” (path/way). Kenjutsu became Kendo, the way of the sword; Jujutsu became Judo, the way of gentleness; Kyujutsu became Kyudo, the way of the bow; and so on. Soon, the art that came from Okinawa became Karate-Do, the way of empty hands.

Karate-Do has undergone a series of developments since it ceased to be an art form restricted to Okinawa. Previously, training consisted of practicing a few katas exhaustively for years=. So much so that master Anko Asato had the philosophy of “one kata, three years”, such was the rigor of the training and the depth of study within a single kata. However, when it became widespread and taught in schools, the teaching method needed some improvements to make it more palatable and easy to learn. This is where kihon (application of basic techniques in sequence) and modern forms of kumite (application of techniques against an opponent), which together with kata formed the tripod of modern methodology.

It was also during this modernization that Karate-Do gained a sporting aspect in some schools, with competitions and championships. Furthermore, some techniques more geared towards this type of competition, such as mawashi geri, were incorporated.

And with all this, the art of empty hands was ready to conquer the world. And it did. Since its consolidation in Japan, the art has been spreading to all continents. Currently, according to the World Karate Federation (WKF), there are more than 100 million Karate practitioners. But with the large number of organizations of the art spread throughout the world, of different lines, not to mention the independent schools, the number is certainly much higher. And, if it depends on us, because of all the good that Karate-Do has to offer, the number will grow much more.

And the rest is history. There is much more to tell, because Karate-Do is rich, diverse and very interesting, with a lot to discover and share. But that will be for the next posts.

_________

The best way to learn about and understand Karate is to experience it firsthand. That’s why we invite you to enroll in a dojo and start practicing.

Karate and health, balance and quality of life!